Benjamin Franklin was, no doubt, the most cosmopolitan

member of the Convention, the first American of international renown, a member

of the Royal Society, many colonies’ former agent in England and the former

U.S. minister to France, where he played a critical role in treaty negotiations

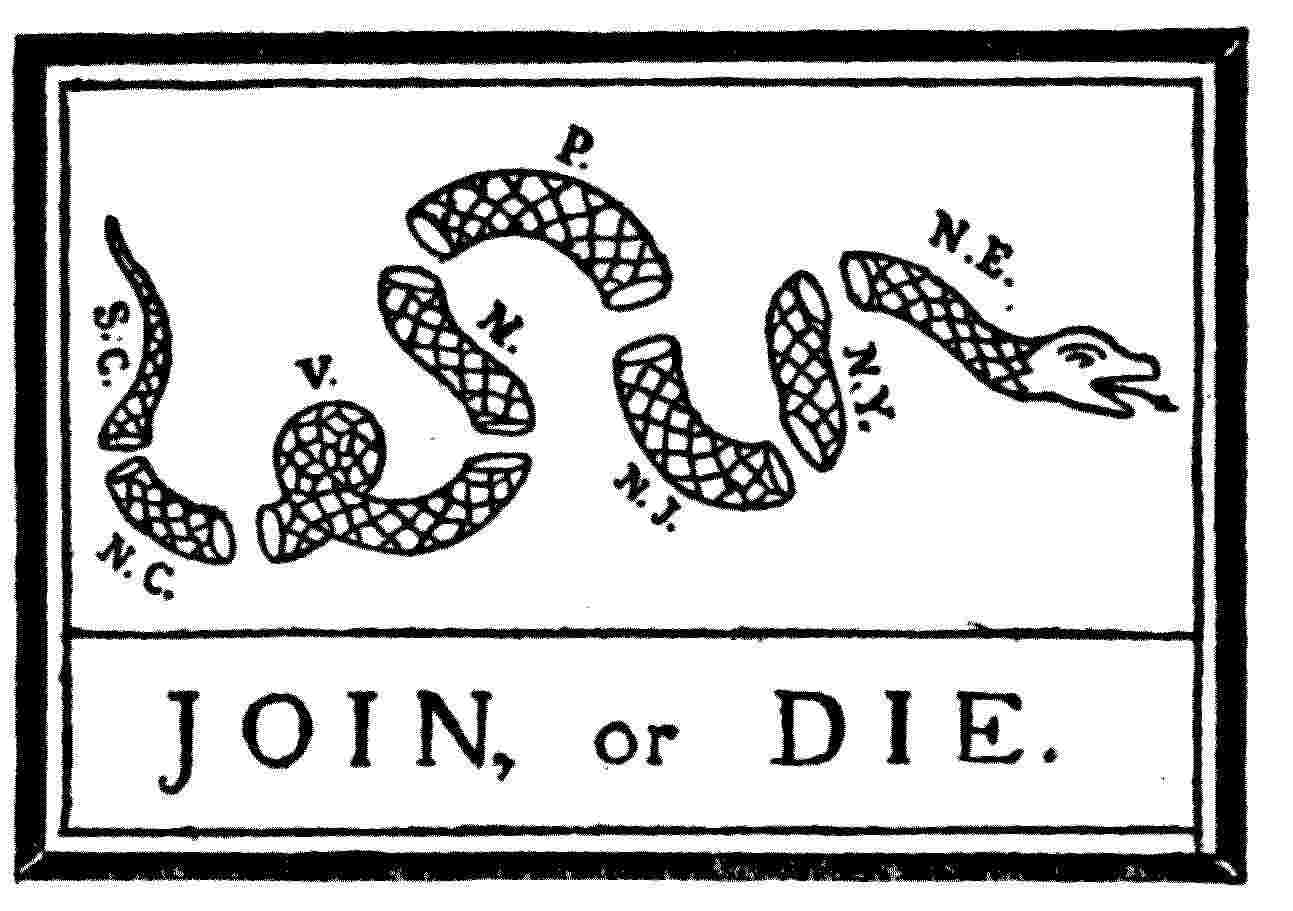

and mingled with the top literatti (in England as well). Franklin had been urging the colonies to

“Join or Die” since the 1750’s, so he would seem a natural nationalist, who

would urge his fellow delegates to look beyond their local interests to the

good of the whole. And no doubt this was

his natural inclination, but instead his statesmanship took the form of

resisting that natural inclination and working, instead, to reassure the small

states and reach the compromise that save the Constitution.

He indicated his natural inclination, saying he would prefer to see each

representative consider himself a representative of the whole rather than an

agent for a particular state, and it would not matter how representation was

apportioned. Since this was not realistic, he favored

representation in proportion to population and voting as individuals, rather

than by states. He did not see this as

threatening to swallow up the small states any more than Scotland was swallowed

up by a union with England. In the

interest of equalizing states, he even offered to give up a part of

Pennsylvania to Delaware and New Jersey, but, he said, this would not be a good

long-term solution since populations are constantly shifting, which would

require state boundaries to be constantly shifting as well to maintain equality.

As a

compromise, he proposed for the smallest state to volunteer to provide whatever

quota of money or force it could afford and have all others agree to furnish an

equal portion. Congress would then

consisted of an equal number of representatives from each states, who would

vote as individuals, rather than by states.

If more supplies were required, Congress could make up the difference by

requesting voluntary contributions from the larger and more powerful states,

which he believed they would be willing to furnish. He apparently considered equal representation

by states as just so long as each state was financing the system equally. What he considered most unjust was the system

of voting by states. Under that system,

the majority of each state’s delegation, in effect, cast that state’s

vote. Since larger states generally had

larger delegations than small ones, it would be possible for a measure favored

by a bare majority of the seven smaller states’ delegations to pass, even

though unanimously opposed by all the large states, and a distinct minority of

members of the legislature could prevail over the majority.

This

proposal was made when the Convention was debating whether representation would

be by population or by states in either house, or even whether to have

two houses at all. Later, when it became

apparent that there would be two houses and that the lower house would be

proportional to population, he proposed a similar system for the Senate:

If a proportional representation takes place, the small States contend that their liberties will be in danger. If an equality of votes is to be put in its place, the large States say their money will be in danger. When a broad table is to be made, and the edges of the plank do not fit, the artist takes a little from both, and makes a good joint.

He proposed instead to have an equal number of

representatives per state in the Senate, each voting as individuals. In all matter involving the sovereignty of

individual states or the overall powers of the central government, each state

would have and equal vote. In all

matters related to spending, states would have a vote in proportion to their contribution

to the treasury. In fact,

however, the large states never said anything to indicate that they were

resisting equality in the Senate for fear that it would tax then excessively;

their arguments were based on the principle that every person should be

equally represented and the practical argument that unless

representation was in proportion to a state’s actual importance, the government

would be hopelessly weak.

Franklin

served on the committee that first proposed the Great Compromise, to have

states equally represented in the Senate in exchange for giving the House sole

authority to originate money bills. This

compromise was apparently his proposal, and he made clear that

he considered these two conditions dependent on each other and would not

support them separately.

His main other contributions on centralization were to propose a federal

authority to cut canals, and, at the end, to urge everyone to

support the Constitution, despite having some doubts abouts it because a stronger

government was clearly needed (9/17/87, pp. 653-654). As the delegates proceeded to sign the

Constitution, Benjamin Franklin gave the most famous statement of then

Convention. George Washington, presiding

over the meeting, had been sitting in a chair with a sun painted on

it:

|

| Washington's Chair |

I have, said he, often and often in the course of the Session, and the viscisitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whenter it was rising or setting; But now at length I have the hapiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting sun.

No comments:

Post a Comment