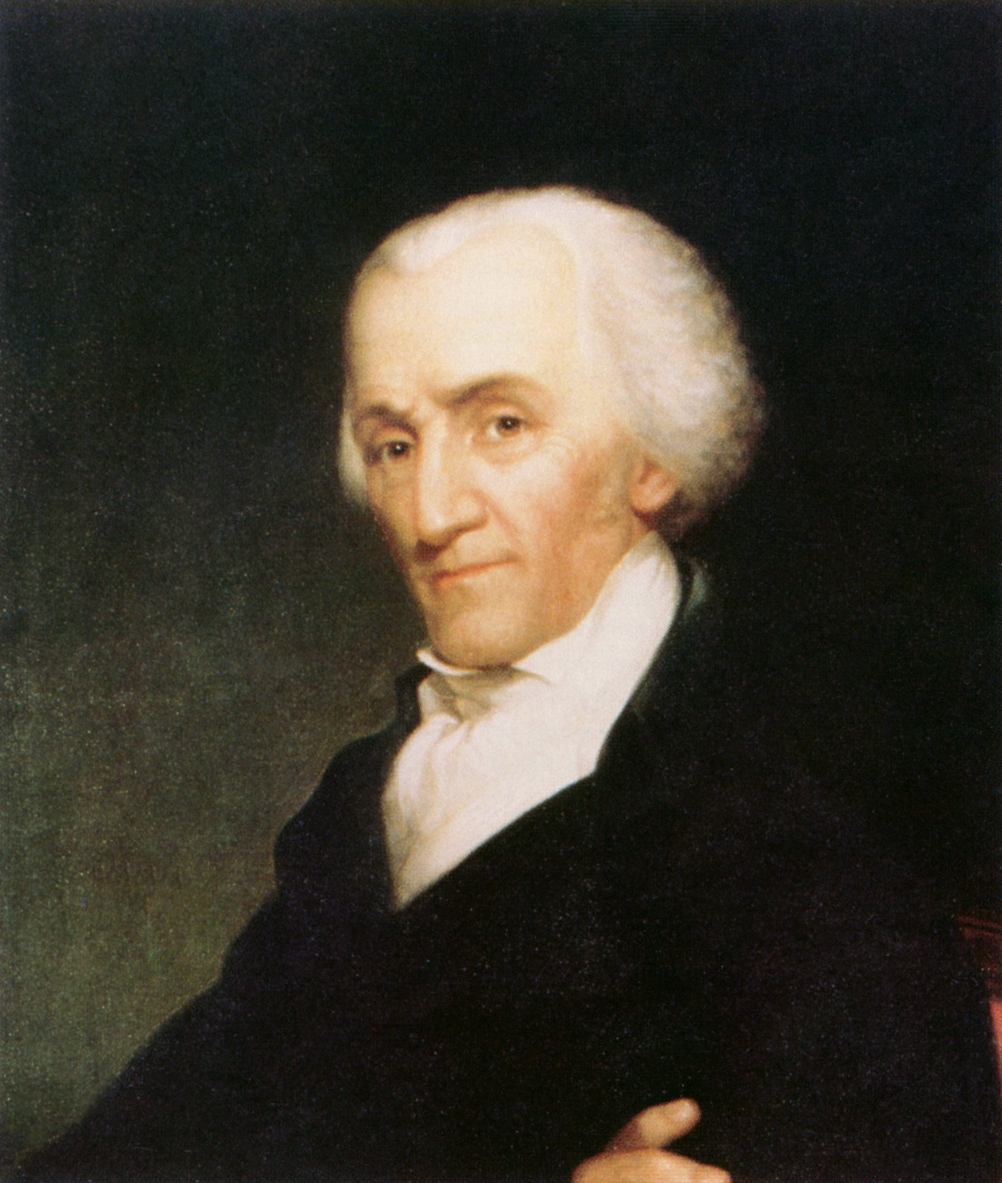

[W]e never were independent States, were not such now, & never could be even on the principles of the Confederation. The States & the advocates for them were intoxicated with the idea of their sovereignty. He was a member of Congress at the time the federal articles were formed. The injustice of allowing each State an equal vote was long insisted on. He voted for it, but it was agst. his Judgment, and under the pressure of public danger, and the obstinacy of the lesser States. The present confederation he considered as dissolving. The fate of the Union will be decided by the Convention. If they do not agree on something, few delegates will probably be appointed to Congs. If they do Congs. will probably be kept up till the new System should be adopted. He lamented that instead of coming here like a band of brothers, belonging to the same family, we seemed to have brought with us the spirit of political negociators [sic].This appears to be an endorsement of the general concepts of the Virginia Plan -- a government with authority over individuals, representing the people as individuals. Gerry served in the committee that first proposed the Great Compromise. He grudgingly assented in its report, saying, "We were however in a peculiar situation. We were neither the same Nation nor different Nations. We ought not therefore to pursue the one or the other of these ideas too closely." Unlike some other moderates, Gerry did see giving the House sole authority to initiate money bills as a significant concession. If Senators voted as individuals instead of by states, he would reluctantly support the compromise, rather than risk seeing the country split apart.

Otherwise, Gerry was deeply mistrustful of the central government and outspoken in his opinions. Already distrustful of the whole process, he called federal control of the militia, "[T]he last point remaining to be surrendered. If it be agreed to by the Convention, the plan will have as black a mark as was set on Cain." He would "as lief let the Citizens of Massachussets be disarmed, as to take the command from the States, and subject them to the Genl. Legislature. It would be regarded as a system of Despotism." Although shaken by Shays Rebellion in Massachusetts, he was "agst. letting loose the myrmidons of the U. States on a

State without its own consent." Unlike other moderates, Gerry wanted federal representatives to be paid by the federal government, rather than the states. On the other hand, he opposed allowing federal authority to establish forts in states. He opposed dividing states.

In the end, Gerry refused to sign the Constitution. Among his objections, he listed the power of Congress to regulate elections, the danger that Congress' authority to regulate trade might include licensing monopolies, the power of the legislature to make all laws "necessary and proper," and to raise money and armies without limit.