The subject of religion is closely related to death, and magic is closely related to religion, so it seems reasonable that they would come next.

Religion, of course, was the main motive for emigration for the Puritans and Quakers. Fischer discusses religion in the sense of doctrine and theology in introducing his cast of characters. Religion in terms of folkways means more people’s religious practices.

The Puritans worshipped in bare, unadorned churches they called meeting houses. Their meeting houses were essentially lecture halls with no images, no stained glass, no alter, no communion rail, only a pulpit painted with a giant eye to show God is watching. Meeting houses also served as civic centers, and as arsenals, so there was no fire in the church, even during bitter winter. Services were long, regardless of the cold, consisting mostly of long sermons in both morning and afternoon. These were not (generally) the hellfire and damnation sermons Jonathan Edwards later made famous, but dry and pedantic sermons about obscure passages in scripture. Fischer assures us that the congregation was not bored by these sermons, but how can we believe him when he cites passaged like, "If the whole conclave of Hell can so compromise, exadverse, and diamertricall contradictions, as to compolitize such a multimonstrous maufry of heterclytes, and quicquidlibets quietly, I trust I may say with all humble reverence, they can do more than the Senate of Heaven." (Um, if you say so, dude). Prayers were delivered standing up and were just as long and abstruse. Puritans also sang hymns, with the emphasis on the words and no attempt to harmonize the music.

Cavaliers were High Church Anglicans, which is to say, almost Catholics. Their churches were much more traditional looking. Service was similar to a Catholic mass, with highly formalized liturgy in an established order and hymns sung by trained choirs. Sermons were short and made up only a small part of the service. Traditionally Cavaliers are considered less religious than Puritans or Quakers, but Fischer believes that does them an injustice. The gentry made many expressions of devotion, especially in their wills, kept many religious books, donated or left items in their wills to churches, and kept spiritual journals. Cavalier paid much more attention in their journals than Puritans to rituals, especially the regularity of their prayers. (Fischer often quotes William Byrd II, a Virginia gentleman diarist of the early 18th Century, who regularly records his adventures with women side by side with whether or not he said his prayers each night. He asks God’s forgiveness for forgetting a prayer a lot more often than he asks it for his adventures with women).

Quakers also worshiped in meeting houses, with large windows and whitewashed walls to emphasize the inner light. Their method of worship is well known. There was no clergy, but everyone meditated in silence together and anyone who felt called upon to speak spoke up.

Back countrymen, like Puritans, were Calvinists, but their methods of worship were quite different.* The Anglican church was the established church in most southern colonies. Back countrymen distrusted the Anglican clergy (often with good reason) as corrupt and irreligious, mere adjuncts of the low country gentry. They admired admired learning in their own ministers, but wanted preachers who could appeal to the emotions as well as to reason. They liked hellfire and damnation sermons. They also held frequent field meetings or camp meetings, held outdoors because there were too many worshippers to fit in a church, the sort of worship accompanied by jumping and shouting and other displays of religious enthusiasm. These, Fischer emphasizes, were commonly practiced in the Scottish border area and not products of the American frontier.

Magic

Fischer comments that the differences in the four cultures were not just differences in regional, social, economic or religious background. They were also the result of different in the times of migration. This is especially noticeable in their attitudes toward witchcraft. Keep in mind that witch hunting was at its peak in the 16th and early 17th Centuries, often escalating into all-out hysteria with each accusation leading to ever more accusations. Not to believe in witchcraft was sacrilege. Witch hunts showed a marked decline in the later 17th Century, and by the 18th Century, no educated person would admit to believing in witches at all. Each successive migration showed less interest in witchcraft than the one before.

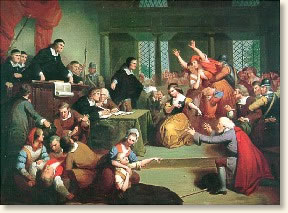

The Puritans, as everyone knows, took witchcraft very seriously. The Devil was a very real presence to them, and they saw the supernatural as dangerous and fraught with evil. They put up signs and markers to ward the Devil off and had frequent prosecutions of witches. In their defense, Puritans hanged, rather than burned, witches, and they usually confined their witch hunts to one or two witches. Only once (in Salem, of course), did a witch hunt spiral out of control in European fashion. Interestingly enough, the Salem witch trials took place in 1692, after witch hunting in Europe had gone into decline. Puritans retains an outdated attitude toward witches.

Cavaliers, the next migration, did not overtly disbelieve in witchcraft, but they regarded accusations with deep suspicion and did their best to discourage them. They were also much less interested in the Devil than Puritan and saw the supernatural, not so much as dangerous or fraught with evil, but as mysterious and inscrutable. Their magical beliefs focused on an attempt to understand it. This led to an interest in astrology and gambling. Virginians were continually betting on just about everything. Gambling was regulated in Virginia, mostly to keep people from gambling away their possessions and becoming burdens on society. Puritans (and Quakers), by contrast, banned all gambling as blasphemous because if God rules the world supreme, there can be no such thing as random chance.

Quakers, at least among the leadership, did not believe in witches or the Devil. They were not, however, always able to suppress beliefs in witchcraft among general populace, and sometime mob violence broke out against alleged witches. Quakers tended to narrow the realm of the supernatural and broaden the realm of the natural. They generally saw the supernatural as kindly and adopted the magic of people who see no menace in the supernatural – spiritualism, seeking to communicate with the dead, and faith healing.

The back country migration was the final one, taking place in the 18th Century when educated people everywhere had stopped believing in witchcraft. Simple and unsophisticated back countrymen retained some vestigial beliefs in witchcraft – how to recognize a witch, how to protect yourself from witches, and even how to put the hex on people – but fighting witches was mostly limited to protective charms. In the many back country outbreaks of violence an vigilantism, Fischer reports, none involved accusations of witchcraft. Their main supernatural beliefs and practices were a set of worldly superstitions, focusing on good luck or bad luck, curing illness and other worldly concerns, like biting off a butterfly head to get a new dress. (For more detail, see Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn). God, the Devil, salvation, spirits and the like played little role.

____________________________________

*Indeed, Fischer often emphasizes the back country culture is not the inevitable result of frontier conditions, but imported from Scotland. His descriptions also make clear that Puritans culture is not the automatic result of Calvinism, but has other origins as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment